Kilcullen once centre of lace

Though there's no remains of it in the town today, Kilcullen apparently was once a major centre of the crochet lace industry in Ireland, writes Brian Byrne.

The craft is reported to have supported up to 700 women workers around Kilcullen in the middle of the 19th century, and is credited with bringing the industry to Clones in Co Monaghan, founding a tradition in that area which continues to this day.

The story of the Kilcullen industry starts with the wife of a local Rector, Mrs Martha Roberts, who began teaching the craft around the mid 1840s to women, to try and alleviate the hardships of the Great Famine.

There had been a tradition of knitting in the area, but there was no longer a demand for it, so Mrs Roberts, according to a letter from her in existence, showed five women how to crochet from a piece which she'd had sent to her from a sister in England.

This was done at a school set up at the Roberts' home in the townland of Thornton, between Kilcullen and Dunlavin, and the deal was that once her initial group had mastered the technique, each had to train three more women in the craft.

The beauty of crochet was that no equipment was needed except thread and a hook that could be home-made. There was also a demand for the kind of relatively cheap lace due to the growth of the middle classes in Europe. For a decade or so, the local business flourished, spreading the brand of Thornton Lace widely as a style in its own right that became highly prized.

According to Chris Lawlor's 'Little Book of Kildare', the industry was so successful that it generated payments of between £100-£300 a month, with the bulk of the workforce coming from the area around Kilcullen.

But the Thornton school was a victim of its own success in a number of ways. The ethos of the school's workers to train others actually resulted in the setting up of competing operations in the different parts of the country. Chris Lawlor feels that the demise of the Thornton business was 'inextricably linked' with the rise of Clones lace, started by workers from Thornton sent there by Mrs Roberts at the request of Mrs Cassandra Hand, wife of local Rector Rev Thomas Hand. Mrs Hand wanted to emulate the Thornton industry for similar Famine relief reasons in her own locality.

According to a history of Irish crochet on 'Irish Crochet Together', they were among 28 Thornton women sent on request by other ministers' wives to various parts of the country

There is also some suggestion that eventually the quality of the Thornton product deteriorated while that in Clones became much better. Also, the Kilcullen designs apparently couldn't be changed quickly enough for buyer fashion changes. There was also the development of cheaper machine-made embroidery and lace, with consequent uncertainties for the hand-made product.

Today, though, Thornton lace pieces are scarce and highly collectible, fetching high prices at auctions for the earlier and arguably better examples. Pieces can be found in good lace museums around the world, and it is generally considered amongst lace experts that the crocheting over cord technique developed by the Kilcullen women contributed a lasting characteristic to Irish crochet generally.

The Guild of Irish Lacemakers notes that Irish lacemaking was promoted by many influential women of the time, including Lady Aberdeen, Lady Erne, and Countess Markiewicz. The product was used extensively by the fashion houses of Paris and London on gowns and evening wear in the latter part of the 19th century, and it was used in men's clothing too, on shirts and cuffs.

Commercial production declined and had virtually died out by the onset of the Great War. Modern Irish crochet is made by individual craftworkers, and is used by a number of international fashion designers, including the Russian master of the style, Julia Tushnicka.

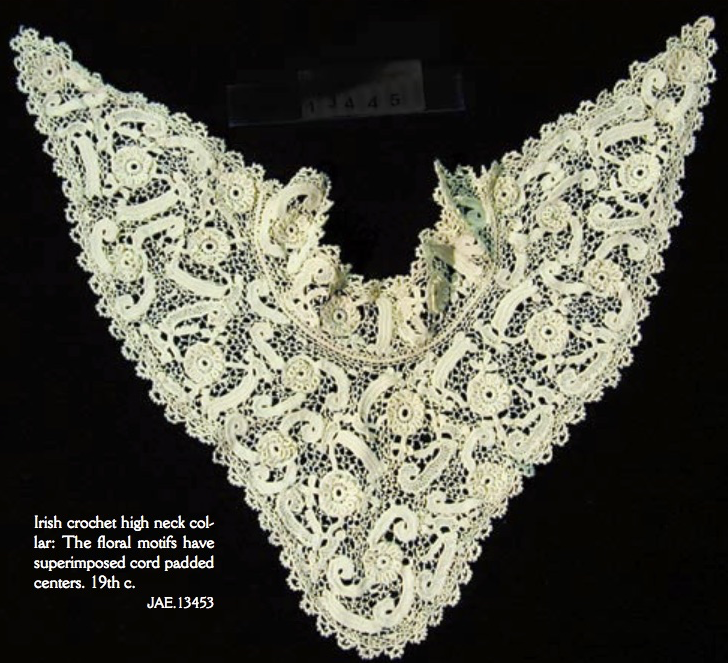

Pictured is an example of 19th century Irish lace, from the Irish Crochet Lace Exhibition in the Lacis Museum of Lace & Textiles, Berkley CA in 2005.

This article was originally published in The Kildare Nationalist.